We had a great online and in-person audience for Ken Chapman’s dissertation defense on Thursday May 8, 2023. Ken gave an excellent overview of his dissertation, as shown below. He will graduate in December 2023.

Congratulations Dr. Chapman!

A pdf of Ken’s presentation is available here.

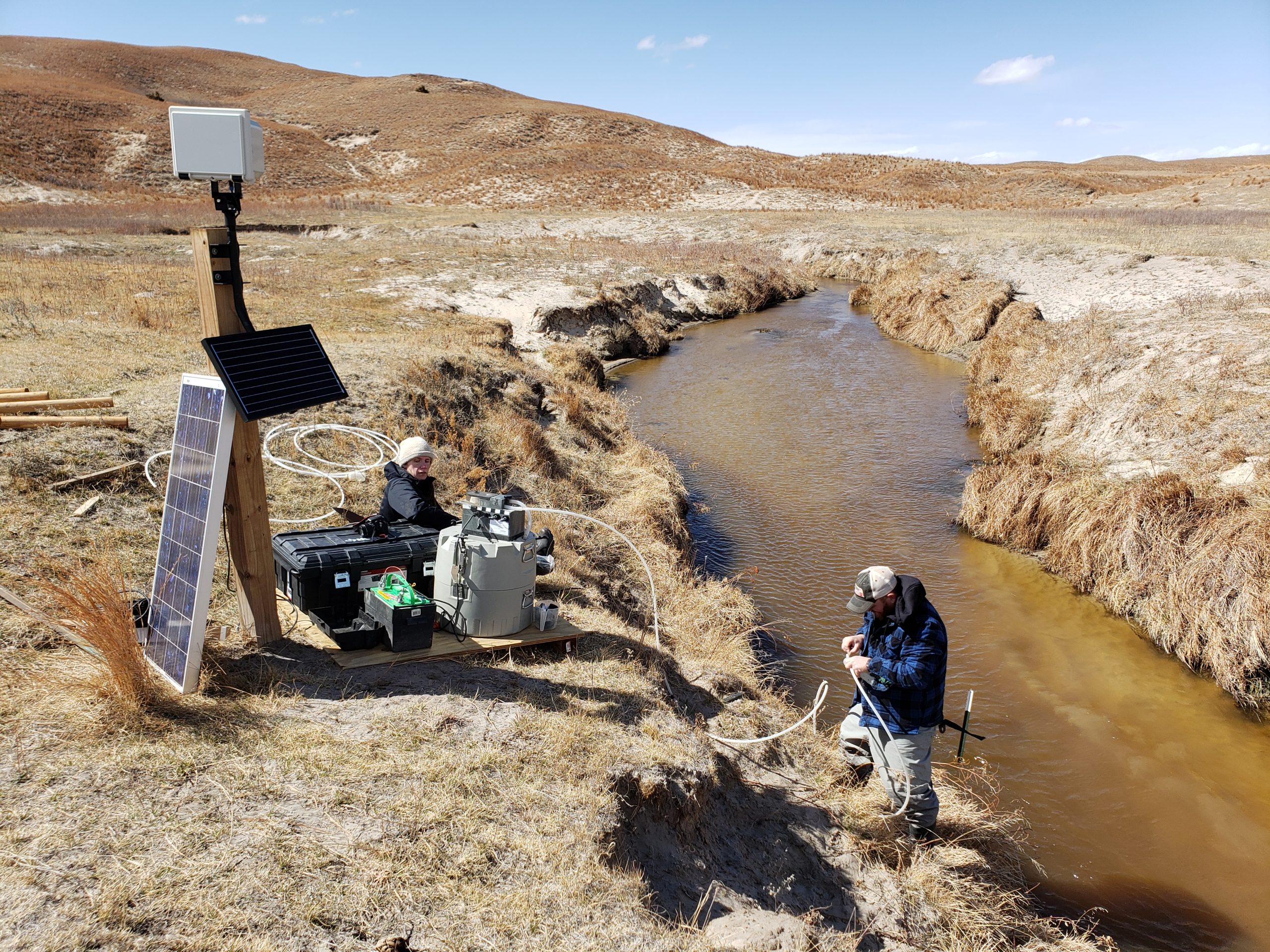

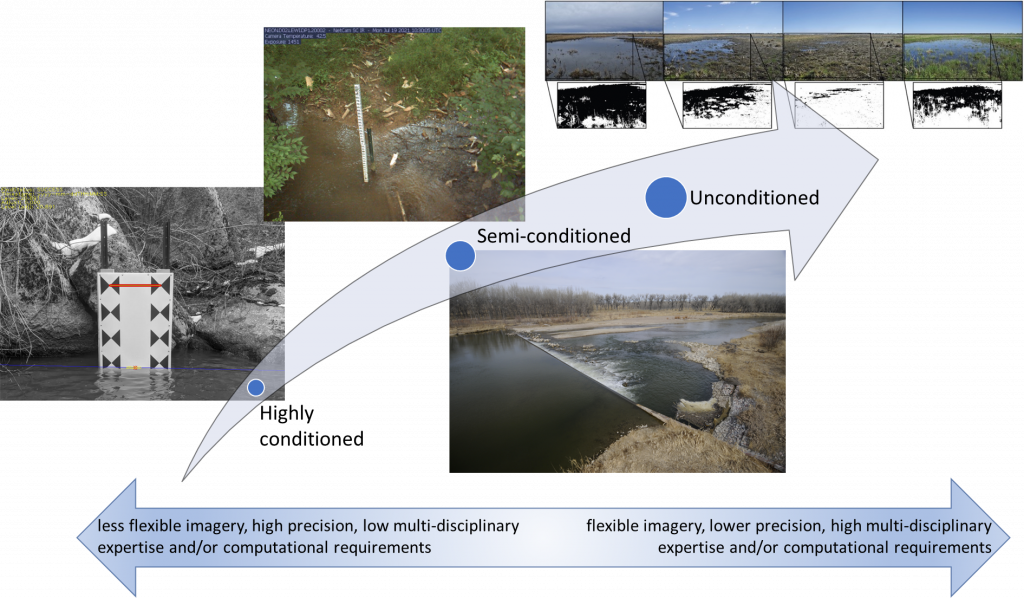

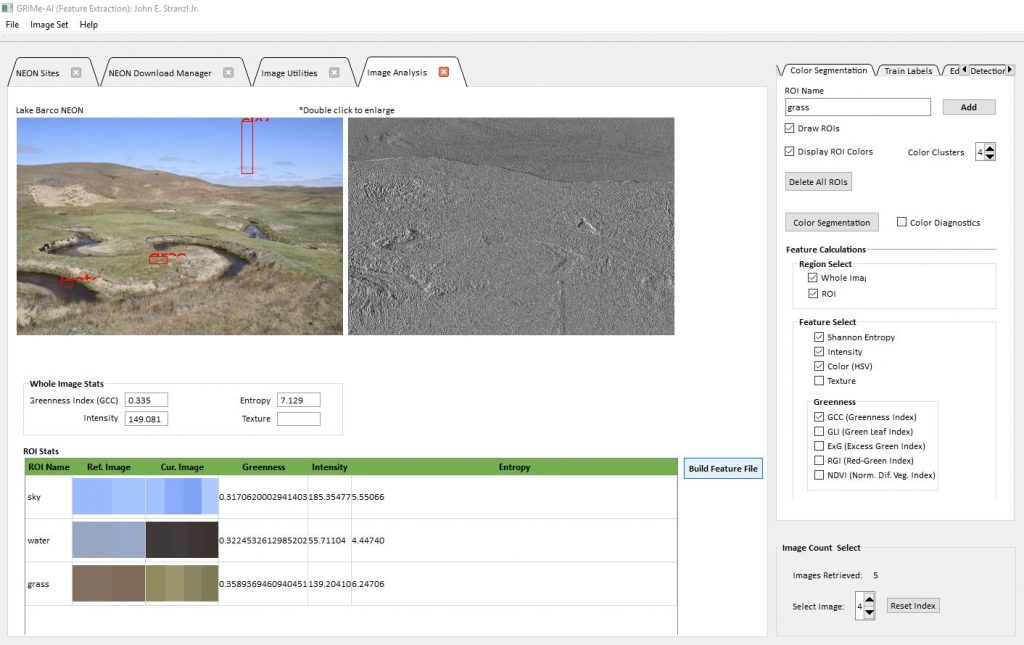

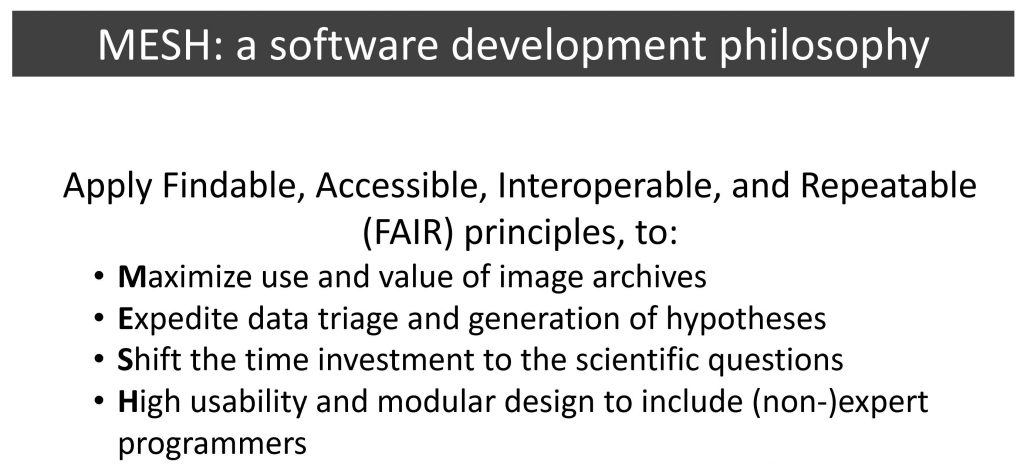

Ken’s three major dissertation projects have resulted in a robust, free open-source water level measurement software and scientific publications.

More information and the GRIME2 software can be found here.

Publications are as follows:

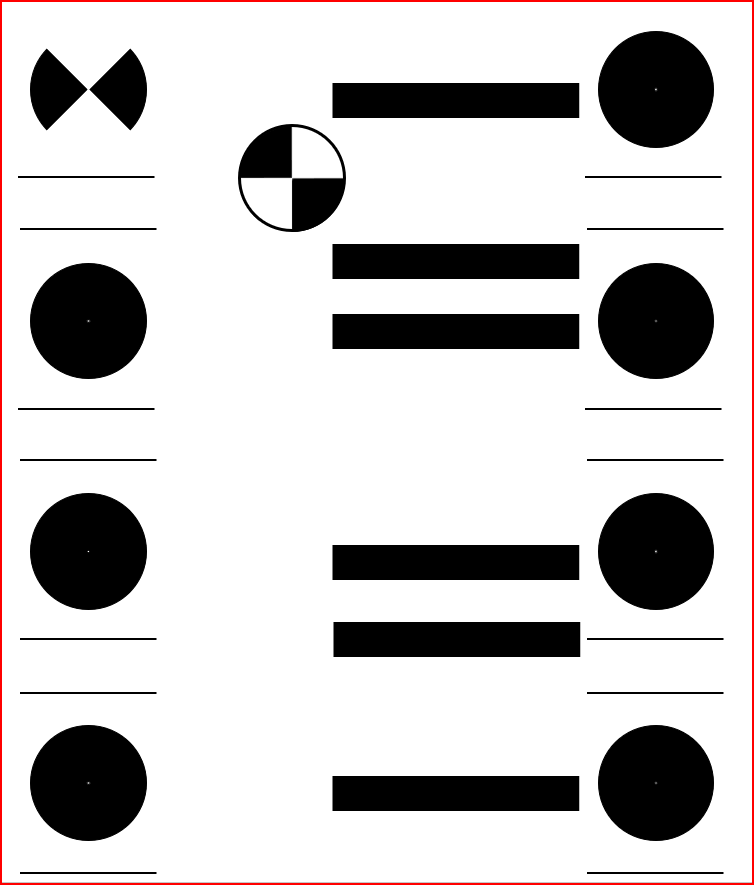

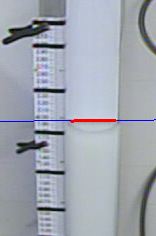

Chapman, K. W., Gilmore, T. E., Chapman, C. D., Birgand, F., Mittlestet, A. R., Harner, M. J., et al. (2022). Technical Note: Open-Source Software for Water-Level Measurement in Images With a Calibration Target. Water Resources Research, 58(8), e2022WR033203. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022WR033203

Chapman, K., Gilmore, T., Mehrubeoglu, M., Chapman C., Mittelstet, A., Stranzl, J.E. (2023). Is there sufficient information in images to fill large data gaps of stage and discharge measurements with machine learning? PLOS Water [revised, in review]

Chapman, K. W., Gilmore, T. E., Harner, M. J., Stranzl, J.E., Chapman, C. D., Birgand, F., Mittlestet, A. R., et al. (2023). Technical Note: Improved Calibration Target for Open-Source, Image-Based Water-Level Measurement. In prep for Water Resources Research.